Scientists show the importance of “putting the brakes on” cytokines to prevent autoantibodies and lupus

A new study has found that rare coding variants in a lupus risk gene could help understand how the immune system mistakenly targets the body's own tissues.

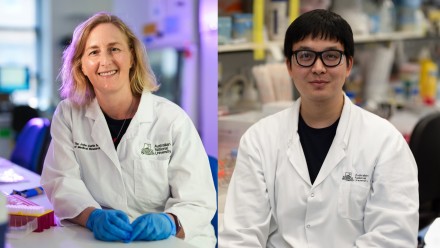

Professor Carola Vinuesa (Image: Jamie Kidston/ANU)

A team led by Dr Julia Ellyard and Professor Carola Vinuesa at the Division of Immunology and Infectious Diseases of the John Curtin School of Medical Research (JCSMR) made this discovery in a study focused on understanding how genetics might contribute to the process of autoimmune disease development. The study was published in the latest edition of the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or Lupus is a complex disease that makes your immune system attack your own body, causing inflammation and damage to various organs. The causes of lupus are not well understood, and this limits treatment options for patients.

Dr Julia Ellyard (Image: Tracey Nearmy/ANU)

Two big factors in the development of lupus are production of autoantibodies and excessive cytokines or responses to cytokines. Cytokines are a group of proteins that function as chemical messengers in the immune system.

“We found that 5% of lupus patients have changes in a gene, SH2B3, that is important for ‘putting the brakes on’ cytokine responses. This gene was already known to be a risk factor for lupus. Our study has demonstrated that these genetic changes mean the immune cells respond more to cytokines and this can promote autoimmune disease” said Dr Ellyard.

Dr Yaoyuan Zhang (Image: Annemarie Steiner)

Dr Yaoyuan Zhang, lead author of the paper said, “B cells are a type of white blood cell that have the potential to make antibodies. Normally these cells are tightly controlled but in autoimmune diseases like lupus they go rogue and produce antibodies that attack our own tissues. We found that because they can respond more to cytokines, these self-attacking B cells that would normally be destroyed are, in fact, able to survive. We think one reason is because they might be able to take up more of a molecule called BAFF that is known to help B cell survival”.

“Survival of self-attacking B cells is known as a break in immune tolerance and is an important step in the development of many autoimmune diseases, not just lupus” he added.

At present, a class of therapies called janus kinase inhibitors are being trialled in lupus patients and these therapies target the same pathway that this gene normally blocks.

“Importantly, our work suggests that SLE patients with these genetic changes may respond well to these therapies,” Dr Ellyard added.

In lupus patients gene variants remove SH2B3, which normally “puts the brakes on” cytokine messages in self-attacking B cells. This increases the B cell survival and allows them to go on to make autoantibodies. In contrast, in healthy individuals without these gene variants these self-attacking B cells are destroyed to prevent autoimmunity developing. Image: BioRender