Most challenging, most rewarding: Doing science as an undergrad

What is the hardest part of doing science?

The answer may vary from person to person. Some might say it’s about developing a good research question; others might suggest it’s getting experiments to work as planned.

To Max Kirkby, a PhB student in his fourth year, the challenge lies in constantly generating hypotheses based on new data and developing elegant ways to prove or disprove them.

“Most of the things we learn and experiments we do in the classroom generate expected results,” explained Max, “So it really challenges me, both as a learner and a thinker, to step outside my comfort zone and grapple with problems that aren’t necessarily well understood.”

“But, at the same time, I think it’s also one of the most rewarding and exciting parts of science,” he said.

A unique path to science

In the past three years, Max has gone through the process of formulating and testing hypotheses in various projects.

The PhB Science program enabled him to participate in multiple research projects in and outside of ANU.

At one point, you would find him studying the effects of exercise on the eyes at the Clear Vision Research Lab, while at another, he would be working on the role of innate immune signalling pathways in dementia at WEHI.

“Being able to experience undergraduate research firsthand and run my own project is something that significantly builds upon my learning in a normal undergraduate degree.”

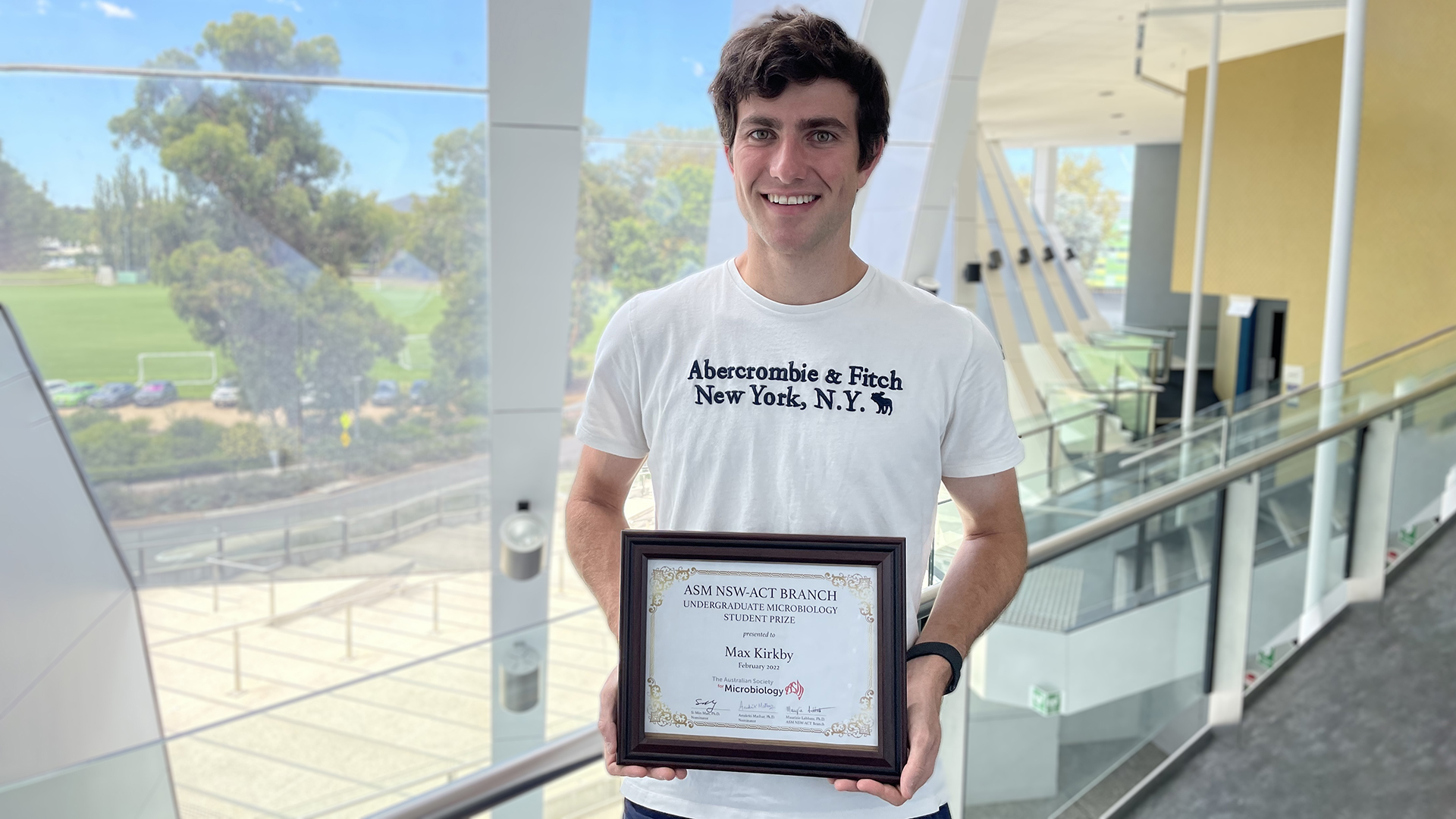

Earlier this month, Max was awarded the Undergraduate Microbiology Student Prize by The Australian Society for Microbiology (NSW/ACT Branch) for his outstanding academic achievement in the microbiology component of his degree.

Now, the undergraduate researcher has returned to The John Curtin School of Medical Research (JCSMR) for more rewarding while challenging science in his one-year-long Honours project.

Under the supervision of Professor Si Ming Man at the JCSMR Division of Immunity, Inflammation, and Infection (i3), Max continues to work on a microbiology-related project, looking at how short strings of amino acids known as immune peptides can help combat antimicrobial resistance.

“I’m excited to get back and do a full year for 2022,” he said.

Mentorship matters

When Max first came to JCSMR for an Advanced Studies Course (ASC) in 2020, he wasn’t sure where his interests in medical research would lie.

He reached out to some older students for advice. “But they didn’t help much because they all said that all the groups were fantastic,” Max said with a laugh.

Eventually, an email from Professor Man led Max to a decision.

“The fact that he responded almost immediately and was passionate about having an undergraduate in his lab when producing outstanding research, really meant a lot to me.”

As a result, Max joined The Man Group and conducted a project investigating the role of NLRC4 inflammasome in cancer.

“JCSMR is a fantastic place for collaboration and mentorship,” he said, “Some of the best ideas and projects I’ve been involved in have been inspired by a quick meeting or email. You never know where such a short, easy thing to do might take you.”

Research suggests that undergraduate research is a transformative experience for many students.

In terms of helping the students clarify their real interests and determine their career directions, mentors play a big part in shaping this experience.

“All of the supervisors I have met at JCSMR are one of the main reasons I came back here for my Honours Year,” said Max, “They would understand the balance between research and regular undergraduate life and also provide opportunities to push my knowledge to the limit.”

“The amount of guidance and support provided by them not only made me a better researcher but also a better person.”

Future ahead

While Max is yet to determine where he will go after finishing his undergraduate degree, he reckons research will be a critical part of his near future.

“I’m interested in the intersection of the innate immune system and neurodegenerative conditions,” Max said.

He believes modern machine learning techniques could enhance research in these fields and drive forward our understanding of their development.

“My overarching career goal is to create an integrative knowledge base that can be leveraged to better understand neurodegenerative conditions and then use that platform to generate translational discoveries in the future.”