Cool science to save cute devils: Honours student targets contagious cancer

In 1996, a Tasmanian devil was spotted in Mt William National Park, Tasmania, its face disfigured by a strange tumour.

No one knew it then, but that sighting marked the first known case of a cancer that would push the species toward extinction.

Since then, the population of Tasmanian devils has plummeted because of this Devil Facial Tumour Disease (DFTD), one of the only known contagious cancers in the world.

The disease spreads through biting—common in devil social interactions—causing aggressive tumours around the face and neck. Infected devils die within months.

By the time the Tasmanian government declared the devils endangered in 2008, DFTD had already spread to more than 60% of the island.

Today, the wild population has collapsed by 80%, under the impact of not one but two distinct DFTDs.

Scientists from all over the world have been racing to understand the fundamentals of the disease and find a way to stop it.

One of them is Yi Ning (Sabrina) Fu, a recent Honours graduate from The John Curtin School of Medical Research (JCSMR) at The Australian National University.

“The Tasmanian devils are the world's largest remaining marsupial carnivore and have a very important ecological niche,” said Sabrina. “And they are cute and adorable—we need to save them.”

For her, the coolest way to do that was through cutting-edge virology.

From spark to science

Every scientist has a moment that sparked their curiosity. For Sabrina, it was meeting her high school science teacher.

“She’s incredible,” Sabrina said, eyes lighting up. “She edited multiple books on the Human Genome Project, and was an editor for Nature. So cool!”

That moment ignited a passion for science that would shape her academic journey.

By Year 12, she was already reaching out to influenza researchers in the U.S., diving into literature on flu vaccines, and comparing seasonal versus universal vaccine effectiveness.

Later, as a Bachelor of Philosophy (PhB) student in Science, she bounced between research projects like an explorer charting new worlds.

You might have found her sitting in a lab tagging proteins to study transmembrane delivery, catching honeybees on summer afternoons to study the potential effects of Varroa mite infestations, or engineering bacteriophages and soil bacteria to tackle heavy metal pollution.

“I’ve always been drawn to projects with real world applications. But if there’s a common thread,” she chuckled, “it’s that I found them all so interesting.”

For her Honours project, she saved the coolest—and hardest—one for last.

A virus to fight a cancer

At JCSMR’s Viruses and Immunity Group, Sabrina spent months infecting Tasmanian devil cells with a virus.

The lab, led by Professor David Tscharke, had previously identified a virus strain that replicated more effectively in Devil Facial Tumour cells than healthy ones.

This made it a promising candidate for an oncolytic therapy: a virus designed to selectively kill cancerous cells.

The million dollar question remained: how safe and effective would this virus be as a treatment for DFTD?

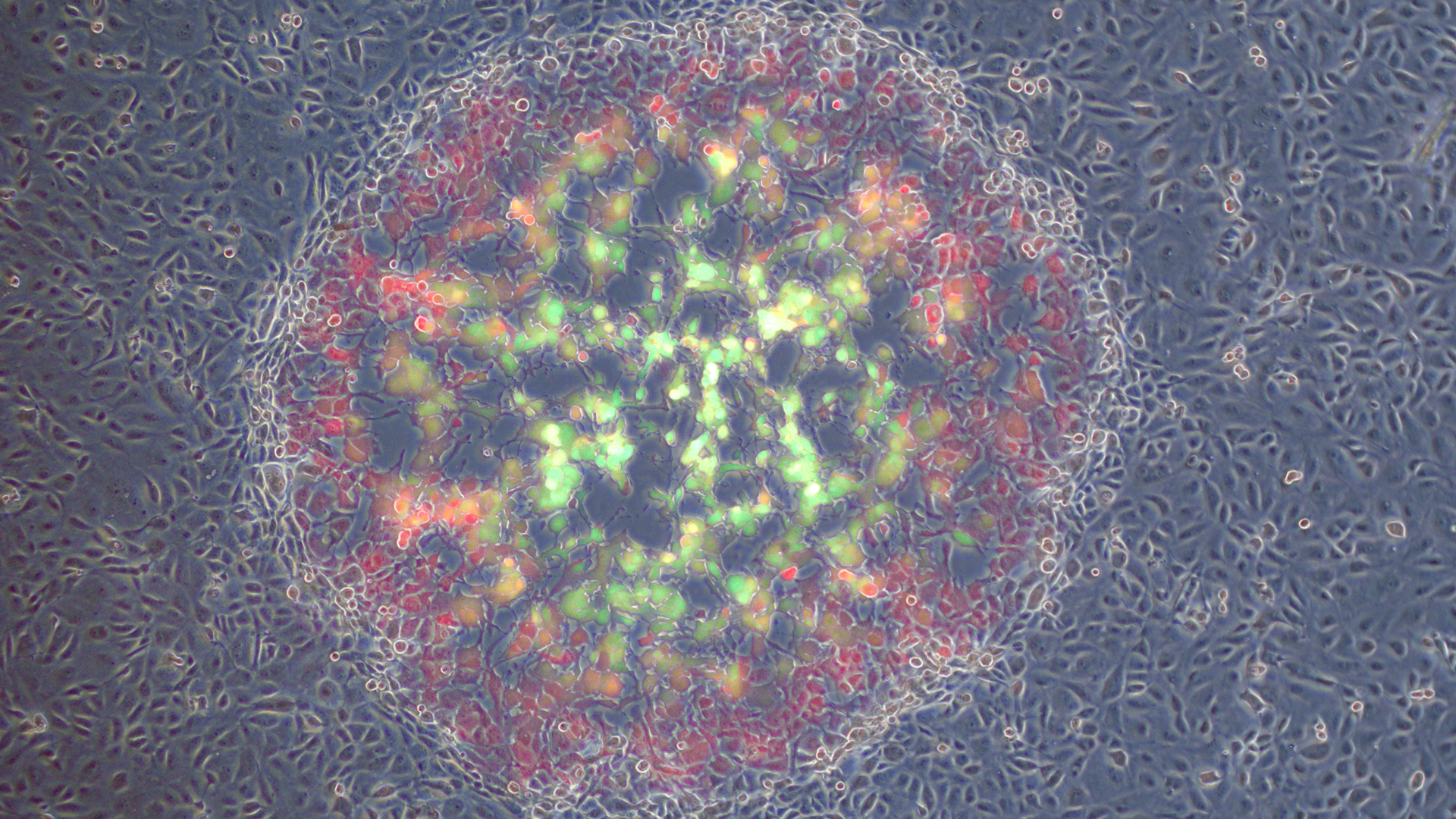

To characterise the process of viral infection in different cells, Sabrina engineered a version of the virus with dual fluorescent reporters to track gene expression in real time.

“Previously, we only had single colour viruses that just showed whether a cell was infected,” Sabrina explained.

“Now with the dual reporter virus I developed, we can distinguish between early and late viral gene expression—two distinct stages of infection.”

By analysing the fluorescence at different time points, researchers could now see how the virus infects tumour cells compared to healthy ones.

Sabrina’s work also identified key host factors that either promoted or suppressed viral replication, offering new insights into the mechanisms of the potential virotherapy.

“If I had more time, I’d love to test this in a model that better mimics what happens in the devil,” she said. Some studies have implanted devil tumours into immunodeficient mice to see if potential treatments can shrink them.

“But ideally, it would be really cool to do it in a non-immune deficient model,” she added.

“Rather than actually killing the tumour, the current goal is making a ‘cold’ tumour go ‘hot’ to activate immune responses against it. I'd love to go more down that path.”

Seeing it work

After an intense eight-month Honours research journey, Sabrina’s work earned her a University Medal for her outstanding academic excellence.

“The fact that it worked was a pleasant surprise,” said Sabrina.

“There were a lot of times where I felt too stupid to be in science, where I struggled for weeks with making everything work,” she admitted, “Imposter syndrome hit hard.”

So when her project came together, when she held a thesis that she was happy with, it meant something deeper to the young researcher.

“Being able to tell myself that I did it was the most rewarding bit.”

Her mentors and colleagues weren’t as surprised, though. They had seen a pattern in Sabrina—before committing to any project, she did an exhaustive deep dive.

Before her Honours year, she had multiple meetings with potential supervisors, carefully weighing her options.

“I want to really know what I'm setting myself up for. I don't want to start something and not be fully committed,” she said.

With support from Professor Tscharke and her lab mates, she found herself in an environment where she would thrive.

And once she made her choice, she went all in.

“You really need to be dedicated to get the most out of it,” she said, “Immersing myself in the work definitely gave me a better appreciation of all the effort that goes into research.”

That mindset took her beyond just the lab.

What’s next for Sabrina?

In 2023, Sabrina joined the first ANU team for the International Genetically Engineered Machine (iGEM) competition, where they won a Silver Medal.

“It was a very different experience because it was so startup focused—thinking about products, intellectual property and scaling up,” she recalled, “It gave me a whole new look into industry.”

Now that she has graduated, she’s taking a year to explore before her next career move while she continues working in the virus lab.

“PhD is definitely an option. So is industry, more R&D-type things,” said Sabrina, “For now, I want time to think about what excites me the most.”

“A big life motto is being flexible and going with the flow—and still researching,” she smiled.

“And of course, to help save the devils!”