PhD student won awards at ASI Clinical Translation School

When your immune system turns against you, is there a way to turn it back to normal?

In general, the answer is no.

While symptoms can be managed using immune system-suppressing drugs, the underlying autoimmunity—immune response targeting self-tissues—is to date, unfortunately, incurable.

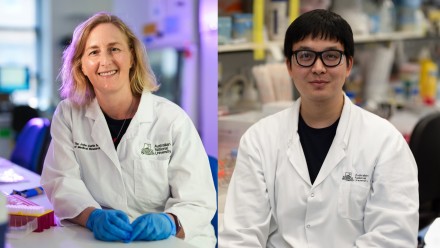

PhD student Cynthia Turnbull looks to be part of the force that challenges the status quo.

At the Centre of Personalised Immunology (CPI), she and colleagues aim to tailor effective treatments for patients with severe forms of autoimmune disease by identifying and understanding the genetic modifiers of the disease.

Recently at the inaugural ASI Clinical Translation School, a conference hosted by Australian and New Zealand Society for Immunology, Cynthia presented her approach and work to achieving this goal to immunologists and clinician researchers.

Focusing on a patient with severe immune dysregulation, Cynthia spent her PhD trying to pinpoint the genetic drivers of the patient’s disease. Through comprehensive genetic tests, she identified a possible disease-contributing mutation in a gene named DECTIN-1.

Studies on the mutation suggested a novel role of the DECTIN-1 protein in regulating the levels of a group of specialised immune cells called regulatory T cells.

Thanks to a CPI database, which holds gene sequencing results from patients with autoimmunity across the world, Cynthia has recently identified two more patients with that specific DECTIN-1 mutation but with different forms of autoimmunity.

“We are planning to look at the immune cells of these patients to see if they share any cellular similarities or disease features with my patient.”

In the longer term, the researchers may be able to group patients with autoimmunity with DECTIN-1 mutations and design more targeted treatment plans.

More importantly, investigations into rare autoimmunity cases as such may shed light on the mechanisms by which common autoimmune diseases develop.

Cynthia’s talk sparked many exciting questions and comments on her project from researchers in the audience. It was recognised as the Best Presentation and won the People’s Choice Award of the conference.

“I felt very surprised and honoured,” said Cynthia, “Such commendations from my fellow students but also clinicians and lab leaders on my work was very touching and unexpected.”

During the three-day conference, Cynthia also learned from people who focus on drug development and clinical trials.

“I was able to step back and see the big picture of immunological research and identify all the ways my project could be applied,” she said.

“I am more motivated to branch into clinical translation as my career in immunology progresses.”

To Cynthia, the ASI Clinical Translation School served as a perfect merge of clinical practice and research projects. The discussions and idea exchange between basic and clinician researchers provided her with an eye-opening experience.

To achieve the goal of disproving the statement that autoimmunity cannot be cured, she asserted, collective efforts by all parts, from bench to bedside, are indispensable.

“This will help us extend our research from the lab to the many patients who need more effective treatments,” said Cynthia.